Ahh, Kubernetes. I love Kubernetes; well, kinda. It’s a complicated but very well designed and written piece of software that appeals to all the old-school Object Oriented neurons in my head while making the rest of my mind go ‘what is happening?’.

Aside from the mad name (which is pain to spell if you have to type it more than one hundred times in a design document/slide deck, hence the casual abbreviation to K8S which I will, thankfully, use from now on) the whole K8S thing really appeals to me; mostly from a design perspective as when you get under the covers, which is what I will (probably badly) try to explain in this post, it’s deliciously simple and clever.

However, as anyone who has battled to install and maintain a non-OpenShift version (excuse the flag waving, I’m a massive OpenShift fan and would be even if I wasn’t an employee of Red Hat), “Kubernetes is Hard (C)“.

When I first delved into it as part of OpenShift 3 it was a complete mystery to me, so I spent a little bit of time reading the design documents for it and after that…..it was still a mystery to me.

But then I started to use it, or more appropriately, I started to craft the YAML for K8S objects as part of the OpenShift demos I was giving. And then, when CoreOS produced the brilliant Operator Framework, which I will also have a stab at explaining in this post, it suddenly became clear as to what K8S was doing under the hood and how.

So, let’s start with the basics; K8S/OpenShift are actually three things. You have a control plane, which you as a User talk to via the RESTful APIs provided. You have a brain, which contains the ideal state of everything that K8S maintains (more in a second) and you have Workers, which are nodes where ‘stuff runs’. Your applications run on the Workers; we’ll leave it at that for now and come back to it in a sec.

So, with the brain of K8S; this contains a set of Objects. These Objects are of a set of defined types; every object in the brain has to one of these types. Easy example; you have types of ‘oranges’, ‘lemons’ and ‘limes’. In the brain you have instances of these, But the brain, in this case can only have Oranges, Lemons and Limes.

When you interact with the control plane, you can create, modify or delete these objects. You do not interact with the objects; you ask the control plane to operate on those objects.

And this is where it gets cool; so, for every object that the control plane supports (in our daft example oranges, lemons and limes) there is a Controller – put simply this is a while-true loop that sits in the control plane watching the incoming requests for any mention of the object it owns; in our pithy example the control plane would have an orange controller, a lemon controller and a lime controller.

When the control plane receives a request the appropriate controller grabs it; the controller can create the objects, change the state of the objects and delete the objects within the brain. When an object is created, modified or deleted within the brain the control plane will act to reconcile that state change; physical actions are performed on the Workers to reflect the required state in the brain.

Deep breath. And this is what makes K8S so cool; each and every object type has its own control point, the brain reflects the state as required by the controllers and the combination of the control plane and the Workers realise those changes,

Now, with the Workers there’s a cool little process that sits on every one called, cutely, a Kubelet. This is the action point; it takes demands from the control plane and physically realises them, and reports back to the control plane if the state deviates from the state the brain wants.

This fire-and-forget, eventually-consistent distributed model is a wonderfully architected idea. It takes a while to get your head around it but when it clicks it’s a wonderful ‘oh yeah…..’ moment.

So, talking a little more technically – when you talk to the control plane you send object definitions via a RESTful API. K8S uses the object definitions to decide which controller to inform (not quite the way it works, think of it as a event/topic based model where al the controllers listen on a central bus of messages; the type of message defines which topic the event lands in, the controllers take the events off the topics – interestingly the reconciliation process works identically; responses from the kubelets arrive as events as well; the whole system works around this principle which is why it is so well suited for the distributed model.

And this is where Operators come in; Operators were the last piece in the puzzle to making K8S extensible without breaking it. I’ll give an example of this from personal experience; OpenShift 3 was a really nice enterprise spin of K8S; Red Hat added some additional objects for security, ingress and the like and to do that it had to produce Controllers for those objects and inject them into the core K8S.

This was problematic; K8S, as an Open Source project, churns a lot; innovation is like that, so to produce a stable version of OpenShift a line in the sand had to be drawn; the K8S version would be taken, the new controllers added to the code base, the binaries spun, tested, released. And every time a new version of K8S dropped the whole process would need to be repeated. In essence a Frankenstein K8S would have to be brought to life every time OpenShift wanted to onboard a newer version of K8S.

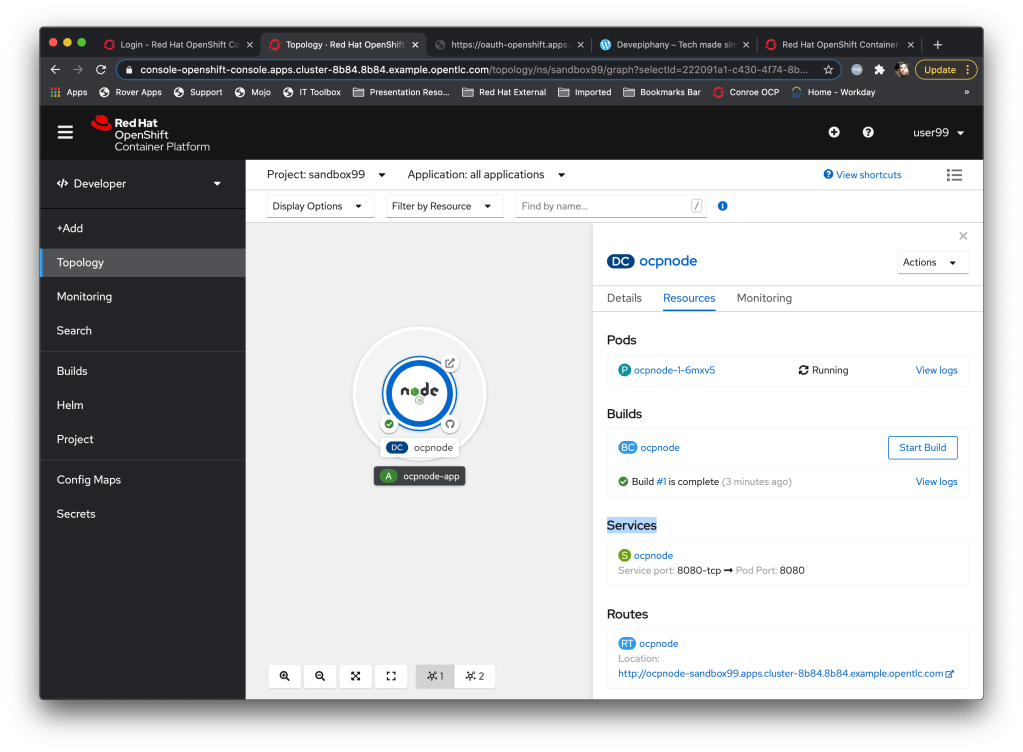

So CoreOS came up with this incredible idea for allowing Custom Controllers to be written and executed that ran as applications on K8S as opposed to being embedded in the core controllers. In English lets say we add a Pineapple object to our K8S knowledge; in the old days we’d have to add a controller into the control plane, effectively polluting the codebase. Now we run an Operator that sticks up a flag that says ‘anything Pineapples is mine!’.

Now, when the control plane receives any object requests around pineapples they don’t go into the event bus for the K8S controllers but instead are intercepted and processed by the Pineapple Operator; it uses the brain as the controllers do, but only to store state information about Pineapples.

This clever conceit meant that suddenly your K8S implementation could handle any new Objects without having to change the core controller plane.

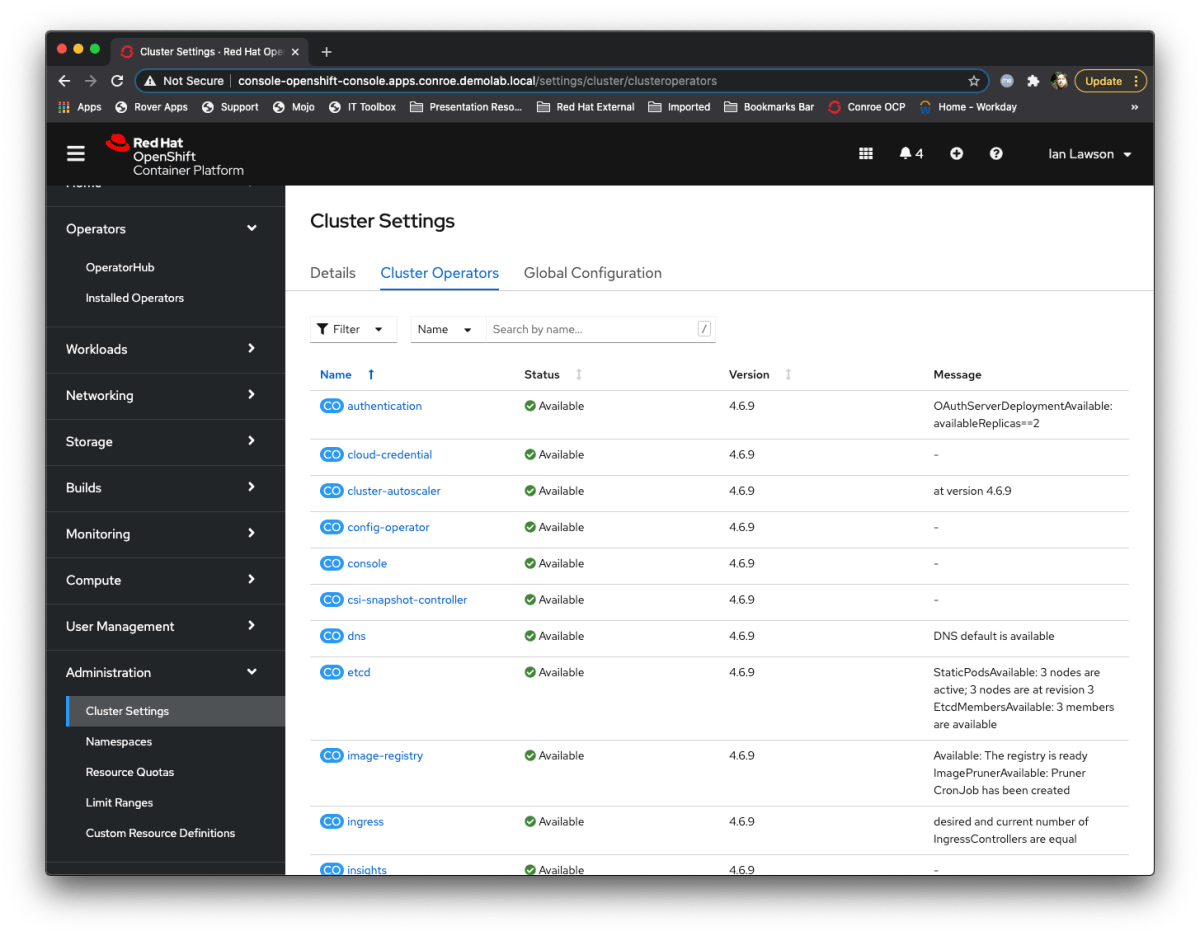

It gets better – the entirety of OpenShift 4.x is implemented as Operators (that operate at the Cluster level). So all the good stuff OCP adds to K8S is done without impacting or altering the core control plane.

I like it a lot because the mechanisms by which Operators work means I can write Operators, in my favourite language, JAVA, which exist outside of the OpenShift cluster; the Operators announce themselves to the control plane, which registers the match of object types to the Operator, and then sit and listen on the event bus – they don’t run *in* OpenShift at all, which is great for testing without impacting the cluster.

One last thing on Operators – how many times have you had this issue when deploying an application?

Me: The application won’t start when I deploy the image?

Dev: Yeah, you need to set environment variables I_DIDNT_TELL_YOU_ABOUT_THIS and WITHOUT_THIS_THE_APP_BREAKS

That little nugget of configuration information lives in the Devs head; there’s nothing in the image that tells me it needs those (we developers tend to get over-excited and documenting stuff is last on the post-it list of jobs we don’t really want to do).

The beauty of Operators is, when written properly, they can encapsulate and automate all of those ‘external to the app’ configuration components; the job of an Operator, as with any controller in K8S, is to configure, maintain and monitor the deployed objects/applications – now a dev can write a quick Operator that sets up all the config, external linkage and the like that is essential to the application, and the Operator will enforce that.

Day Two ops and all that lovely CICD goodness……

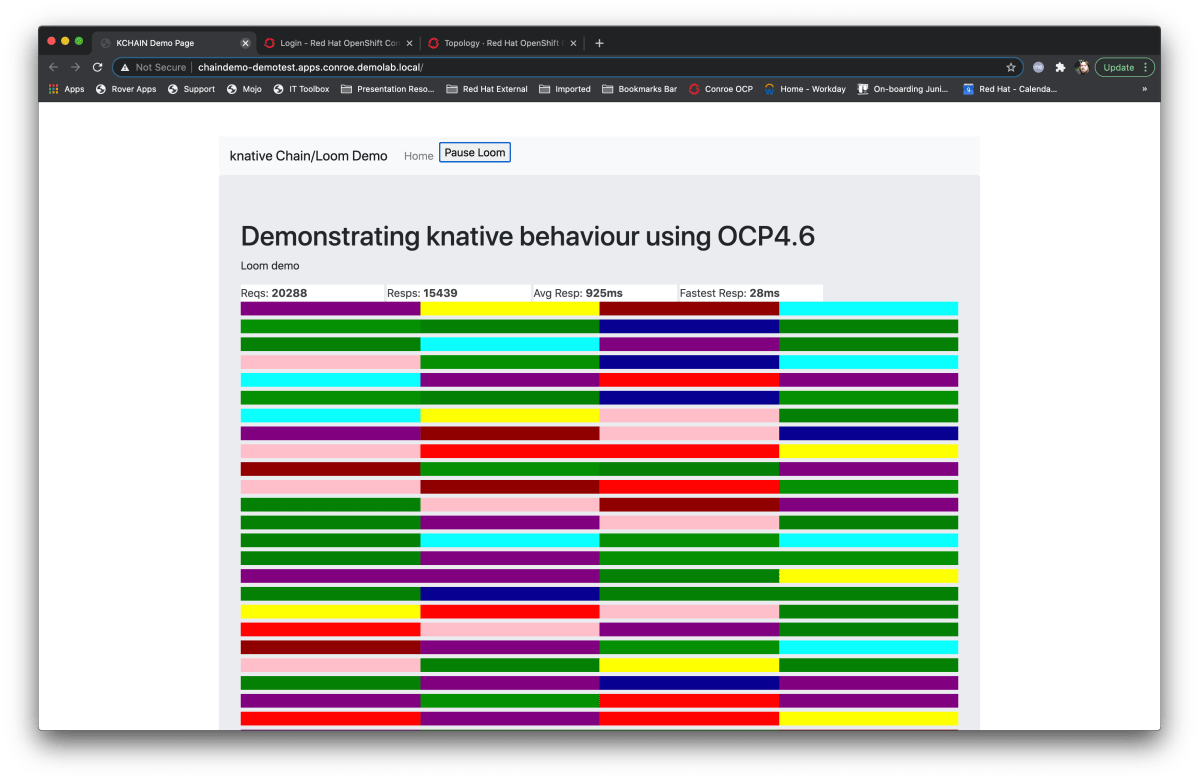

Anyway, thanks for sticking with this stream of consciousness; I needed to do it as part 2 of the Knative blog posts talks about Operators…..